What is Aquaponics?

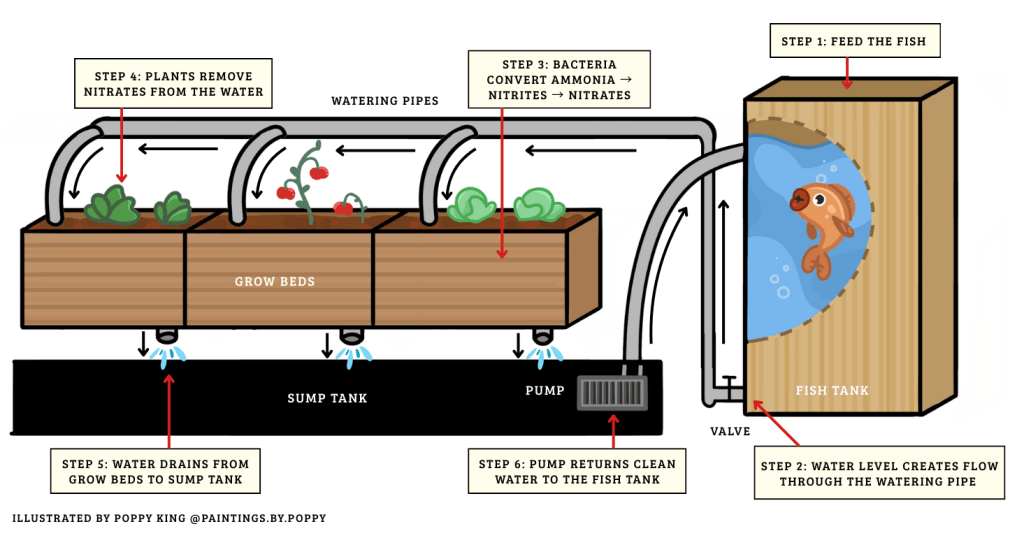

Aquaponics is a closed-loop system that combines aquaculture (raising fish) and hydroponics (growing plants without soil) in a symbiotic environment. The key player of aquaponics is naturally occurring bacteria that are responsible for converting nitrogenous waste produced by fish into readily available nutrients that can then be absorbed by plants. The plants, rooted in a soil-free medium such as clay aggregates, filter and clean the water, which recirculates to to the fish tank creating a self-sustaining, water-efficient ecosystem. This efficient integration of biological processes makes aquaponics an environmentally friendly and scalable solution for sustainable food production.